Meeting languages on their own terms (Gawain & The Green Knight)

Below is one of my favourite passages from the Pearl Poet's Gawain and the Green Knight, a 14th-century English poem written in a Cheshire dialect:

After Crystenmasse com þe crabbed lentoun,

Þat fraystez flesch wyth þe fysche and fode more symple;

Bot þenne þe weder of þe worlde wyth wynter hit þrepez,

Colde clengez adoun, cloudez vplyften,

Schyre schedez þe rayn in schowrez ful warme,

Fallez vpon fayre flat, flowrez þere schewen,

Boþe groundez and þe greuez grene ar her wedez,

Bryddez busken to bylde, and bremlych syngen

For solace of þe softe somer þat sues þerafter

bi bonk;

And blossumez bolne to blowe

Bi rawez rych and ronk,

Þen notez noble innoȝe

Ar herde in wod so wlonk.

Pronunciation:

- 'ȝ' is 'gh' as in 'enough' (if this displays improperly, imagine a '3').

- 'þ' is 'th' as in 'the'

- 'y' is pronounced like 'i' in 'with'.

Here's some basic modernisation:

After Crystenmasse came the lonely lent season,

Which tests the flesh with fish and food more simple;

But then the weather of the world fights with winter,

Cold clings down, clouds lift up,

Brightly falls the rain in warmest showers,

Falling upon fair fields, flowers there showing,

Both the ground and the groves being green of clothes,

Birds hasten to nest, and sing beautifully For solace of the soft summer that follows thereafter

by hillsides;

And blossoms swell to blow

By hedgerows rich and thick,

And then glorious notes

Are heard in woods so noble.

The simplified version is easier to grasp for a modern reader, but the economy of language, rhythm, and feeling of these words in the mouth & ears is absent. The Pearl Poet was attentive to these qualities to such a degree that synonyms of a given word will regularly appear in the selfsame line. The result is a maturity of composition making other great poems of the era such as The Castle of Perseverance sound almost amateur by comparison.

Some notes here:

- fraystez or 'fraist' is a test of strength or resolve, often in a form of physical attack.

- busken is like 'hasten' or 'busy oneself'.

- bolne means 'swell' in much the same slightly medical manner we might now mean.

- wlonk means "noble" in the sense of class or quality of behaviour, sometimes used to refer to the quality of a season or natural feature or location.

- The 15th century Awntyrs off Arthure contains the line "To þe wode are thay wente, the wlonkeste in wedys, Bothe the kynge and the qwene." -- "the king and queen went to the woods in their finest clothes". Note 'wedez' (clothing) appears above also.

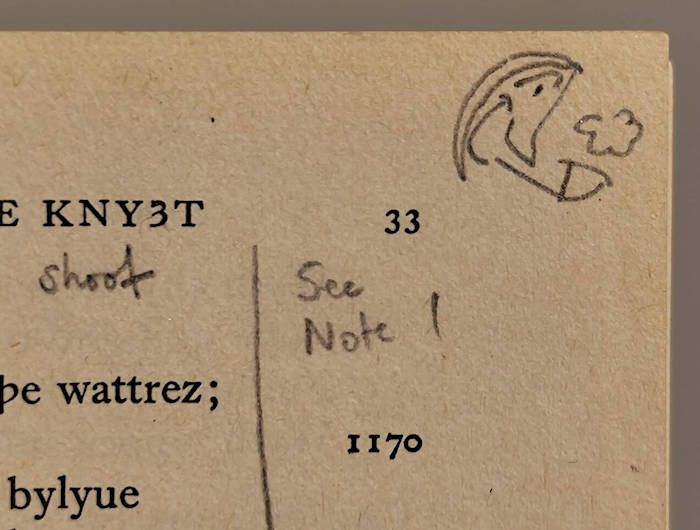

Here's margin notes appended:

After Crystenmasse com þe crabbed lentoun, | cold/unsociable

Þat fraystez flesch wyth þe fysche and fode more symple; | tests/challenges

Bot þenne þe weder of þe worlde wyth wynter hit þrepez, | contends

Colde clengez adoun, cloudez vplyften,

Schyre schedez þe rayn in schowrez ful warme, | bright/white

Fallez vpon fayre flat, flowrez þere schewen, | fields

Boþe groundez and þe greuez grene ar her wedez, | greaves, clothes

Bryddez busken to bylde, and bremlych syngen | birds hasten, gloriously

For solace of þe softe somer þat sues þerafter | proceeds/follows

bi bonk; | hillsides

And blossumez bolne to blowe | swell

Bi rawez rych and ronk, | hedgerows, thick/luxuriant

Þen notez noble innoȝe

Ar herde in wod so wlonk. | noble/beautiful

This kind of marginalia is unsuitable for screens. My whimsical side has a little parasocial friendship with Mr. David Woodward of St John's College, who, in addition to plentiful dictionary annotations, made little drawings of a pipe-smoking moon in my copy of Gawain. Whenever I struggle with a page, I feel as though I have a friend reading along with me.

Tolkien's modernisation:

Tolkien understood the Pearl Poet well - his translation is semantically faithful, and the glossary & notes to the original with E.V. Gordon and Norman Davis are superlative in quality. His modernisation by necessity forces poetic English of the 1300s into the structure and logic of that of the 1900s:

after Christmas there came the crabbed Lenten

that with fish tries the flesh and with food more meager;

but then the weather in the world makes war on the winter,

cold creeps into the earth, clouds are uplifted,

shining rain is shed in showers that all warm

fall on the fair turf, flowers there open,

of grounds and of groves green is the raiment,

birds are busy a-building and bravely are singing

for the sweetness of the soft summer that will soon be on

the way;

and blossoms burgeon and blow

in hedgerows bright and gay;

then glorious musics go

through the woods in proud array.

Rhythm and alliterative stresses differ significantly, particularly the 2nd line and also in the more contemporary, inappropriately sing-song and affected 'birds are busy a-building and bravely are singing' ("bravely" is also a slightly slanted word choice but I shan't be a bully).

Heavily on relies word order for natural sounding sentences Modern English; many of these sentences' stresses are shifted by stricter modern grammatical patterns obliging being-verbs to appear in specific places.

- Bot þenne þe weder of þe worlde wyth wynter hit þrepez

- But then the weather in the world makes war on the winter

The original's 3rd line mixes 'th' and 'w' such that it alliterates on both across the line, using wyth to tie the two together after a bracketing beginning and ending full of 't' sounds (boT Thenne ; hiT Threpez).

- Boþe groundez and þe greuez grene ar her wedez

- Of grounds and of groves green is the raiment

The original is bolstered with the plural form's 'ez' to further give the sentence consistency, to tie better wedez with grevez. Greves rhymes with wedez and raiment does not with groves. Line #5 ends with a 'w' in 'warme' and #7 with 'wedez'; lines #6 and #8 sibilant with 'schewen' & 'syngen'. Tolkein doesn't catch any of this, and bar rhythm I do wonder why something more like Both the grounds and the groves, grene are their clothes was not chosen. But, I think these insufficiencies are partly Tolkien, and mostly his task.

Simon Armitage's modernisation:

Armitage borrowed Tolkien's heavily, but changed words and phrases too obscure. Armitage focuses on the feeling & telling of the story, rather than on semantic faithfulness:

after Christmas there came the sullen Lent

that tests the flesh with fish and food more meager;

but then the weather in the world makes war on the winter,

cold creeps back into the earth, clouds are uplifted,

shining rain is shed in showers that warm

and fall on the fair fields, where flowers open;

on grounds and on groves, the earth's clothing is green,

birds are busy building and boldly are singing

for the sweetness of the soft summer that will soon be on

the way;

and blossoms shimmer and show

in bushes bright as day;

their colors like melodies flow

through woods in grand display.

What I want to emphasise is that it was not only the story itself that made the Pearl Poet significant when re-discovered in the 19th century; it was the technical proficiency with which it was written using the language of the time.

'Bolne' means 'swell', emphasising something gradually growing from within and usually used to reference things like pride, pus-filled boils and sexual excitement. The original was blossumez bolne to blowe. Tolkien chooses "blossoms burgeon and blow". Burgeon is semantically closer, having also archaic meaning of "to bud" and a modern meaning of expanding rapidly (often regarding industry or business), but "burgeon" and "bolne" do not have the same auditory qualities; "bolne" and blowe" both contain a strong 'l' sound complimenting blossumez, alliterating smoothly. The 'zh' of burgeon is harsher and lacks the same smoothness, for that Modern English lacks a suitable substitute.

For Armitage, the 'sh' in shimmer & show merges smoother - shame it is while fantastical an inferior image. The Pearl Poet writes on the changing of the seasons here in a grounded manner. In the poem, the passage of a whole year taking place in a single paragraph is contradistinguished with 6 prior describing the Green Knight's horse & clothing, and another ~6 of a supernatural event taking place. The Green Knight --a stand-in for Christian-shunned Paganism's Nature, witchcraft, and the base desires of man-- waits in winter to deal Gawain an ax-blow. That the season then changes so rapidly that it passes in a near-instance, and that the blossoms are described at the beginning and end of their brief life cycle in "bolne" and then "blowe", for me, is not just a narrative fast-forward, but a small but subtle way to point to life's fleetingness, particularly for our man Gawain's trepadation for fearsome circumstances anticipated a year after that supernatural event. In the original each aspect of meaning, poetry, and music are tightly interwoven.

Both translations are good, but neither reach the level of the Pearl Poet. I do admire Armitage not because I think every choice shows perfectly what made this story so great, but because his is a braver endeavour, and is more proper to being his own act of creation; Tolkien's translation, paired with his peerless annotated edition of the original Middle English, is both good poetry and a useful tool; it is an academic effort. Armitage is bold for that he is trying to capture the feeling of the poem for a modern audience over strictly the meaning; a real aspiration when the goal is G&TGK.

I don't think I could effectively modernise Gawain either, but also I don't want to. Rather, I find it is better to persevere with annotations in pencil, or use a tool like what I am making to quickly reference medieval English words, and meet the language on its own terms.