Four snippets on paradigms & perspective

- Moving from typewriters to computers

- Remembering who you're talking to in political disagreements

- Playing video games for the first time

- Looking at chords from funny angles

Moving from typewriters to computers

An engineer/technical editor of a friend once told me of his past company's challenges moving from a paper-based to computer-based editing process in the late 1970s/early 80s.

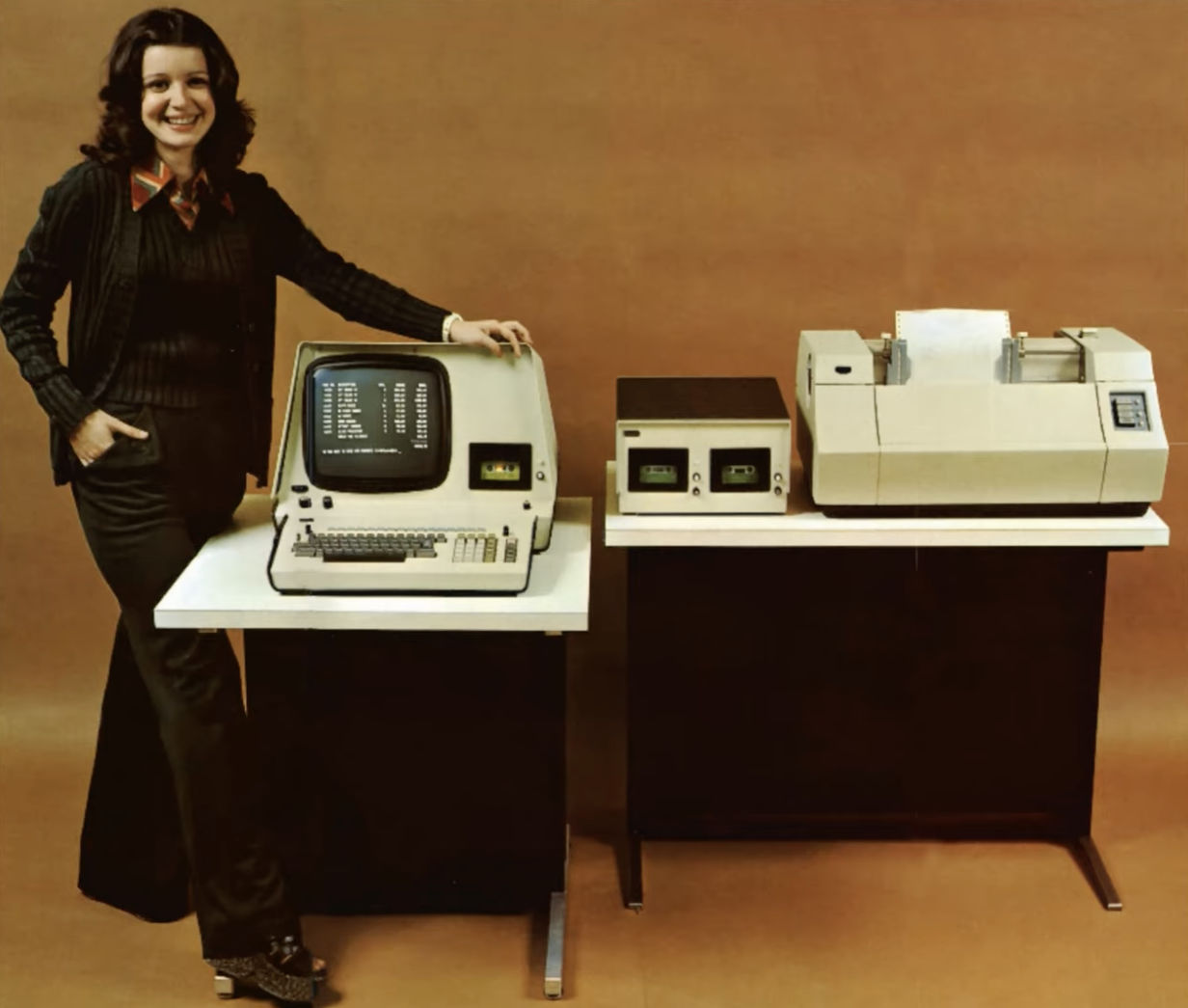

The system used was the Wang 2200 PC, consisting of fixed 12" green monitor and keyboard built into a desk, with a separate processing unit housing twin 8" 64KB floppy disk slots: one disk for the operating system, and the other for file storage. Programmes pre-loaded were a word processor, a database manager, and a spreadsheet program. Here's an amusing advertisement of the Wang system that gets a jab in at Apple.

The company had a team of 2-3 staff who would copy out handwritten documents with mechanical typewriters.

Their workflow was as follows:

- The typists typed up the handwritten documents, and passed them to editorial.

- In pencil the editors noted typos and further changes in pencil on the typed transcription, and returned them to the typists.

- The typists reviewed these notes and corrected the errors by retyping the relevant pages.

- The typists submitted the changed documents to editorial for review once more.

- Repeat steps 2 - 4 until ready for publication.

These typists had no experience with computers and their then-novel textediting interfaces, nor had they undertaken any training. The result of the computer's sudden introduction into the above workflow was that, when the second round of changes was submitted to my friend the editor, he found these typo-corrected documents contained new errors in different places to the first round of corrections.

This scenario may make no sense unless you really imagine yourself without the understanding & experience of computers necessary to know intuitively you don't need to type the whole printout back into the computer's word processor again in a new document for the second round of edits.

Remembering who you're talking to in political disputes

I'm told by a friend that "Given what I know of you and your life circumstances, it doesn't surprise me that you think the way you do" is an excellent wildcard in an unproductive or unstimulating discussion.

Playing video games for the first time

Recently, I began introducing my wife to video games for effectively the first time in her life.

In the third area of Limbo (Playdead, 2010) is a basic physics puzzle wherein a noose hanging from a branch is weighed down by a corpse. The player needs to advance from the lower ground to its left, to the higher ground to its right. The player character's weight combined with that of the corpse bends the branch, pulling down the rope too low to make the swinging-jump from low to high. Beneath the rope and a little to its right, is a draggable bear trap:

The solution is:

- Drag the trap directly below the hanging corpse.

- Jump onto the rope. The combined weight bends the branch, causing the corpse to enter the trap's mouth, releasing the corpse from the rope.

- The branch will now raise high enough to let your character swing up to the higher ground.

Despite my frustration watching the above not being done, the solution is only obvious if you have learned to mentally parse particular elements within a video game's scene as conceptually distinct from that scene's purely decorative elements in their capacity as objects with pre-programmed properties and behaviours as part of a discrete and rigid puzzle system of interactions between different such objects.

Not knowing such a logic, being unfamiliar with WASD controls, and not knowing just how limited the set of controllable behaviours the player character possesses are, what she speculated might be possible in the gameworld and therefore viable as a way to approach the problem, was unbounded. Things like: trying to climb up the edge of the cliff from its base; trying to enter the background and climb up the tree that way; climbing up nearby trees in the foreground to find a path through the tree branches, trying to drag large stones that were actually just part of the environmental foreground graphics.

Looking at chords from funny angles

One of my strongest memories of school is when my guitar teacher took us from playing 12-bar-blues to some basic jazz. We sat down in the gym hall with a whiteboard, covered basic theory for how to build a fruity chord, and then played songs using them. I learned well then how interdependent theory and practice often are.

We were taught this voicing of a G6/9maj7 with some enthusiasm:

e|---2---| F# - maj. 7th

B|---3---| D - 5th

G|---2---| A - 9th

D|---2---| E - maj. 6th

A|---2---| B - maj. 3rd

E|---3---| G - Root

What this teaching led to was enjoying experimenting with/absuing patterns & structures more than learning & playing set songs, often without respect for musicality, and this is probably why I failed to connect to other musicians until I discovered internet forums and also jazzcore.

This particular chord and its voicing are fun. Expressed in different voicings, that E might end up in the 2nd octave, at which point it's more justifiably nothing more than a major 13.

This kind of slightly flexible naming convention in mind, I tried at describing it in different ways. Pattern recognition led me to try breaking this chord into two triads. Technically, if we treat the root as king, then it's a G6 on the bottom 3, and an A6sus on the top, but look, notes are notes and whatever you call it, what this contains is the notes of an Em/G in the lower 3 strings, and a Dmaj/A on the top strings:

e|------2---| F#

B|------3---| D

G|------2---| A

D|---2------| E

A|---2------| B

E|---3------| G

In which case, you can almost logic your way into calling this an Em+D polychord. Whether we're convinced about the name doesn't much matter, because harmonically you can use it that way.

So if you were to write a song composed of chords that can be neatly grouped into lower & higher registers, within each bar alternating between them to a consistent rhythm, would you be writing a song built of polychords, or, if composed right, a song in which you interleave two distinct chord progressions in two distinct keys?

Growing up I was sometimes derided by blues and rock players for using terms like "tone cluster" and "polychord". An older classical guitarist once broke into laughter hearing a band described as "Chinese thrash metal", which is uncontroversial among folks working in the rock/metal tradition (if you're unsure, it's metal, in a thrash style, from China. Maybe there was an erhu player in there too).

I haven't played an instrument seriously in nearly a decade, but I think jazz folk might have the most fun. The last blues jam I went to, 12 different musicians played the same song, 10 times. The last time I heard an orchestra player try to improvise I had to politely applaud afterwards. Jacob Collier's music may be gauche but he might just be in heaven.